(adsbygoogle = window.adsbygoogle || []).push({});

Updated

The 8K/60 fps HDR stream was sent from Tokyo to Los Angeles, CA, Portland, OR, Brazil, and elsewhere over the public internet—and it looked fabulous.

Scott Wilkinson / IDG

Today’s Best Tech Deals

Picked by TechHive’s Editors

Top Deals On Great Products

Picked by Techconnect’s Editors

The 2020 Summer Olympics in Tokyo, Japan, is full of firsts—first Olympics with virtually no fans in the stands, first time the year on all the signage does not match the year it’s actually taking place, first mixed-gender competition (4×400 relay), first transgender Olympian (women’s weightlifting), first Olympics in which the top-ranked contender (Simone Biles) dropped out of all but one event in her field.

Intel demonstrated something of even more interest to TechHive readers, at locations in Los Angeles, CA, Portland, OR, Brazil, and elsewhere: The first time that 8K/60 fps HDR video of Olympic events was live-streamed from Japan over the public internet. This amazing feat was accomplished using Intel technology from end to end.

Intel

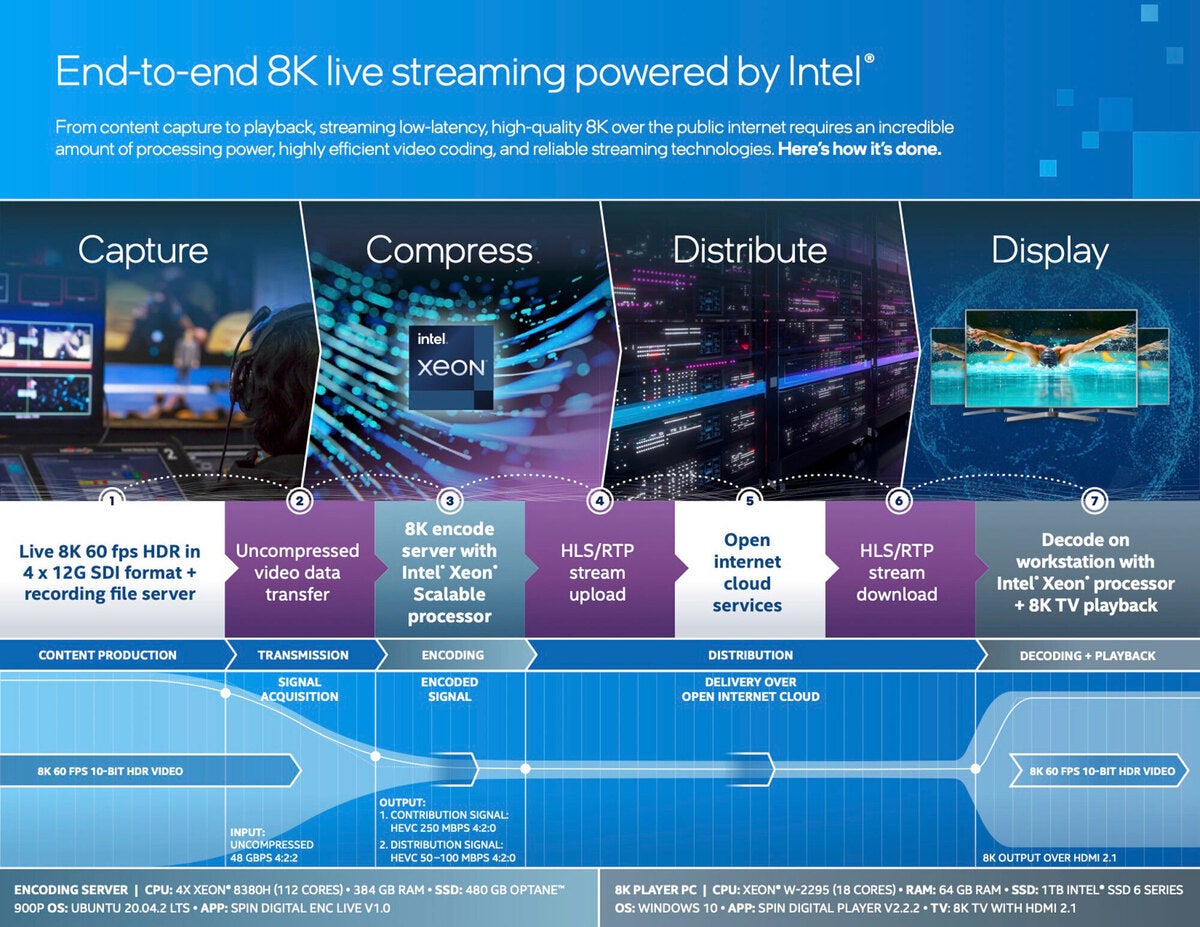

IntelThis infographic details the entire end-to-end process of streaming 8K/60 HDR content on the public internet.

Japanese broadcaster NHK captured footage of various events in 8K (7680×4320) at 60 fps and 10-bit HLG high dynamic range with 4:2:2 chroma subsampling. That raw data, which requires a bandwidth of 48Gbps (!), was then sent via fiber optics to the Olympic Broadcasting Service (OBS), where it was converted to a 4x12G SDI electrical signal.

Next, the signal was encoded and compressed using the Spin Digital Enc Live V1.0 HEVC codec on a server with four Intel Xeon 8380H scalable CPUs and a total of 112 cores running the Ubuntu/Linux operating system. Other hardware included 384GB of RAM and 480GB of Optane 900P SSDs. The HEVC output from the system included a contribution signal at 250 Mbps and a distribution signal at 50 to 100 Mbps, both with 4:2:0 subsampling. Perhaps most impressive, the encoding and compression was performed in real time with a latency of only 250 to 400 milliseconds!

The distribution signal was then uploaded to an open cloud service. Intel wouldn’t identify which one it used, but it could be any such service, such as AWS (Amazon Web Services), Microsoft Azure, or Google Cloud. The stream can utilize two protocols: HLS (HTTP Live Stream), which packetizes the data and uses a variable bitrate, or RTP (Real Time Protocol), which sends the data without packetization at a fixed bitrate.

Scott Wilkinson / IDG

Scott Wilkinson / IDGEach person and seat in this long shot were perfectly clear in 8K. The shadow detail in the upper stands was impressive, and the recap footage in the inset window looked much better than it does in this photo.

I attended the demo in Los Angeles. It was set up in a conference room at the Skirball Cultural Center, which has fiber-based gigabit internet access. The stream was picked up by a gigabit ethernet router that passed it to a Windows 10 PC via Wi-Fi 6E. That computer included one Xeon W-2295 CPU with 18 cores as well as 64GB of RAM and a 1TB Intel SSD. Spin Digital Player V2.2.2 decoded the video in real time, which was then sent to a 75-inch 8K TV via HDMI 2.1 from an Nvidia GeForce RTX 3080 GPU. Here again, Intel would not reveal the make and model of the TV. All told, the latency from encoding in Japan to display in Los Angeles was said to be 2.5 to 4 seconds.

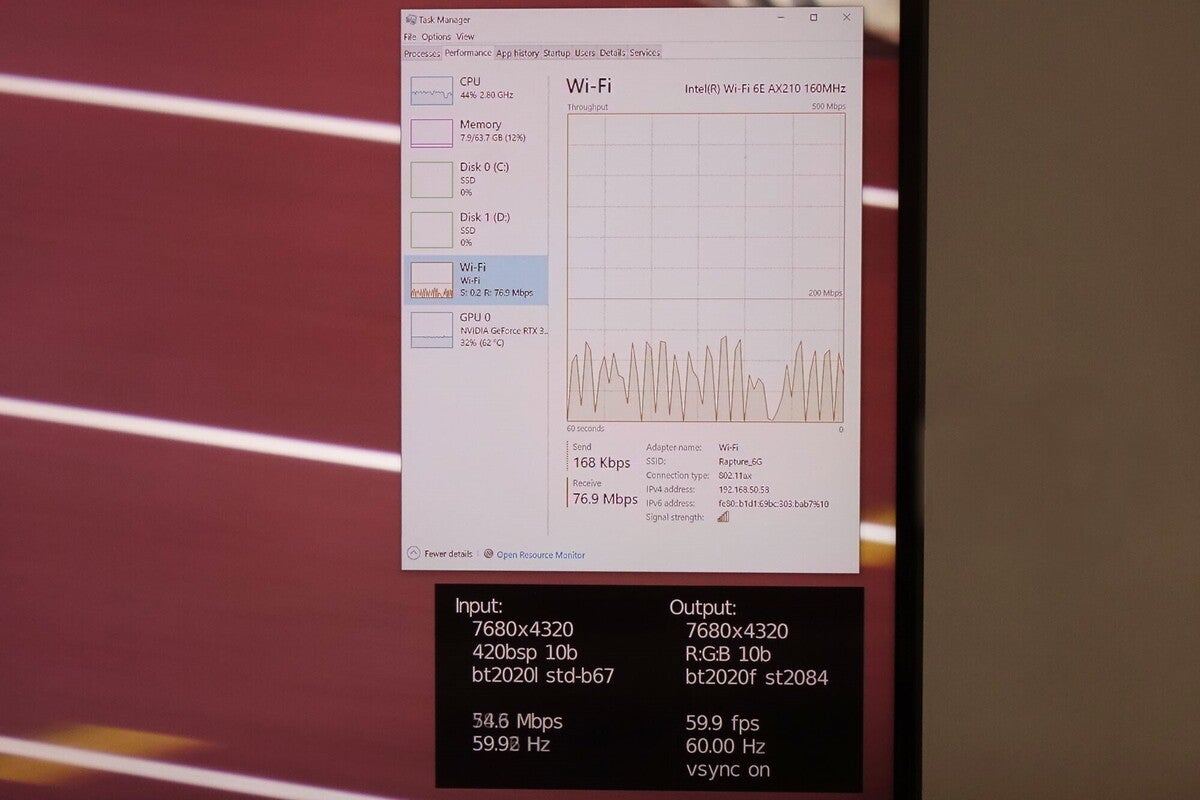

The image on the TV included two windows in the lower right corner with stats about CPU usage, Wi-Fi bitrate, etc. Decoding the HEVC bitstream occupied about 42 percent of the CPU’s bandwidth, while rendering the video out consumed about 32 percent of the GPU’s capabilities. Wi-Fi bitrate varied between about 20 and 100 Mbps because they were using the HLS protocol, which sends packets in bursts. I was told that, for some reason, the RTP protocol didn’t work at Skirball, though it did at Intel’s Portland, OR, facility.

When I was there, it was super-early in the morning in Tokyo, so they were streaming pre-recorded events, including swimming, sprinting, basketball, and skateboarding. As you might imagine, the image was amazingly sharp with loads of detail; I could even read the names on ID badges in medium shots! In longer shots of the stadium, the seats were much more clearly discernable than they would be at lower resolutions, and drops of water that splashed about during the men’s 50m freestyle were razor sharp.

Scott Wilkinson / IDG

Scott Wilkinson / IDG8K provides enough detail to read the tattoos on the winner of the men’s 50m sprint.

One shot showed a side view of the overhead camera suspended with wires at very shallow angles, and I could see virtually no jaggies, even up close to the screen. Notice I said “virtually;” when I was close to the screen, I did see a few minor discontinuities in those wires when they were nearly but not completely horizontal. Still, this artifact was far less pronounced than it would be even at 4K.

The advantages of HDR were not quite as apparent, but they were certainly there. In the indoor stadium shots, the field and lower stands were brightly lit, while the upper stands were not, yet there was plenty of detail up there. Also, the recap footage within an inset window was very bright, yet it did not look blown out at all. When I first arrived, I saw a quick shot of the Olympic cauldron being lit by Naomi Osaka at night, and the flame definitely had more detail than it would in SDR. There were also a couple of shots of the running track with virtually no lights on, and I could not see much shadow detail at all, but that might have been because the demo was in a well-lit room.

Scott Wilkinson / IDG

Scott Wilkinson / IDGThe inset stats window revealed many performance parameters. Here, you can see the Wi-Fi bitrate over time. Because the stream was using HLS protocol, the bitrate jumped around as packets were sent.

The demo was most impressive, leading to the obvious question: Can consumers receive such a stream at home? For those with an 8K TV in Japan, the answer is yes; NHK has been broadcasting 8K in that country for several years. And Globo TV in Brazil has just become an Intel partner, giving Globo subscribers access to the stream. At present, however, there are no streaming-service providers in the U.S. that offer such access. According to Intel, this was a technology demonstration to show what is possible, not what is currently available to most consumers.

Also, keep in mind that decoding the 8K/60 HDR stream required what is essentially a high-end gaming computer that would cost around $4000 or $5000 today. No currently available streaming box or TV with built-in streaming apps is up to the task. But as with all things digital, that will change. Processors get faster and cheaper every year, so it won’t be long until inexpensive consumer products will be able to handle such a stream.

With the increasing availability of 8K TVs, consumers are starting to clamor for 8K content, and if Intel has anything to say about it, they will soon get their wish. All you need is Internet access with a bitrate of 250 Mbps or higher—which is now fairly commonplace–and sufficiently powerful hardware, and you will be able to receive streams such as I saw this week. All that’s left is for content creators and providers to add them to their offerings. Sports programming is a likely first step, and I look forward to seeing it in all its 8K/60 HDR glory very soon.

Corrected August 8, 2021 to remove a reference to NHK using Sony F65 CineAlta cameras for this demo. We were informed after publication that those cameras were used for an earlier 8K streaming demo unrelated to the Olympics. We also added a paragraph about the type of computer that consumers will need today to decode an 8K/60 stream of this nature.

Note: When you purchase something after clicking links in our articles, we may earn a small commission. Read our affiliate link policy for more details.